I developed this method to deal with my own personal writing problems, which are: anxiety, procrastination, perfectionism, and project management. So you may have totally different problems, which this won't help at all for. But if you have trouble getting started on a writing project, get started but then right away look at it and stop because it looks like it's sucking, or have a hard time telling how far there is left to go and end up fiddling endlessly with the easier sections and avoiding thinking about the harder ones, it could help.

My second caveat is that it's only been tested for two 20 minute presentations, one 10 page paper, and (now) one blog entry (this one), and I don't know how applicable it is to longer things (though I strongly suspect it could be used for distinct sections of larger projects). So it should evolve, and I want to hear any ideas you have about how it should.

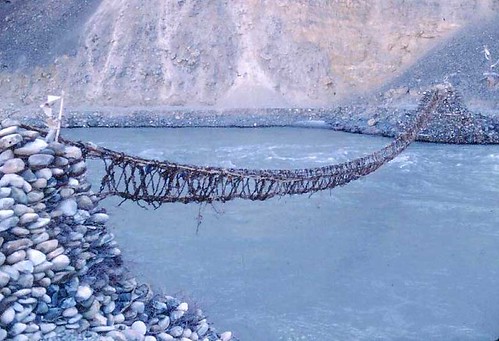

The ropebridge is your very first attempt to sketch out a writing project from beginning to end, and it is meant to be incredibly rough, miles away from a first draft, but structurally complete. It's written using a forwardwriter, some setup where you can only write forwards, never backwards. The objective is to get from the beginning to the end as quickly and fluently as possible, not stopping to perfect or improve anything but just leaving a note right in the text, often in square brackets. Like

That would be as ridiculous as an eeel chasing a aheron [bad analogy , made no sense, thinkgo nof a betwter one to go there]

A great advantage of using a forwardwriter is that the text really looks like a mess, at least if you're as bad of a typist as I apparently am, so your brain knows it's unfinished, and feels uninhibited about the exact wording. A good simple next step after you have a ropebridge is to tell yourself you're just going to copy the ropebridge to a new document and correct all the spelling mistakes. If it works for you like it does for me, you'll find you're doing a lot more than that, choosing better words, rewriting whole chunks and writing all new chunks.

A rope bridge might be flimsy and rickety, with many planks missing, but once you can cross the chasm between having an absolutely blank page and a complete piece of work, you can start to build the real bridge - of concrete, steel, or whatever metaphorical building material you might choose (for me it's rainbows). I got the image of a rope bridge from Douglas Hofstadter's Le Ton Beau de Marot, where he talks about the highly constrained creativity necessary in translating a piece of poetry that rhymes in a foreign language into rhyming english poetry. He said that he always feels less anxious when he gets some rough translation that basically rhymes, like he can relax and be more creative once the chasm is spanned. As my friend Chris said when I explained it to him, "So it's something you could turn into a finished paper over the course of a night, if you absolutely had to."

Failing in writing a ropebridge is very important, and you should let yourself do it - if it isn't going quickly, quit at once. It's a sign that you're not yet ready to really start writing. You need to read more, you need to talk it over with your friends, and you need to do more free writing (thinking by writing, again possibly using a forwardwriter), until the moment is right to try it again. I think part of why this works, and could even produce better writing, is that it focuses on the story of your paper as a whole, the overall flow of the argument, and it forces you to tell the story to yourself first. If you haven't figured out the story, you're not really ready to write a draft.

It should really be doable for projects of the size I say above in about two sittings, around 2-3 hours. It will be skimpier than the finished document, with IOUs in square brackets you wrote to yourself to flesh parts out, but the idea is that each paragraph should roughly match to a paragraph of a hypothetical finished draft. There will likely be passages that you can use almost as is in a real draft, but it could also happen that your first draft contains almost no words in common with the ropebridge. It just acted as scaffolding. On some of those first drafts I opened a completely blank document and just had the ropebridge open at the side as I typed afresh. Other times, as it says above, I start by copying over paragraphs of the ropebridge and "just fixing the spelling".

I see this as a key tool in a larger project of mine, learning how to finish writing projects and other things needing creativity with a steady, easy effort over time, knowing where you are in the project and with no portion so terrifying you put it off and can't face it. A complete rope bridge can give you a readout of where there is serious work to do. Even if you don't solve all the hard writing problems on this one pass, it at least charts a course past where they are. Hopefully it can be followed by another just as easy pass, and then more and more, always making it better and better (this part is still theoretical with me). As a number of my books say, writing is nothing at all like producing perfect crystalline prose when you sit down at the keyboard, but splatting something down there and continuously beating it with a stick - beat beat beat - until it starts to vaguely resemble what you had in mind.

As a last note, this is all about generating just a *first* draft. What happens next is a highly social process which I will write about in a future entry (hopefully by which time I'll understand it more).

4 comments:

This is a great idea. In the graphic arts, a rough sketch is often done to get the general layout of the work before any mark that is intended to be a part of the finished product is put down. Oil painters, for example, will sketch in charcoal, often with mulitple lines to get it just right, and then paint over it. This is the first analogy I've seen to it for writing, and I think it's sorely needed for many perfectionist writers. One thing I do when I find myself obsessing over wording is I put what I want to say in the plainest possible language in comments (I write in latex, so it's easy). It gives me the structure of the work in words I get quickly, and then I can worry later about getting the wording right. As you might expect, saying your point in the plainest possible language is often similar to how you should say it in the final draft.

I completely agree with your idea. In fact, I used to be great at writing outlines. The problem is, and I think it's a new challenge to your forward writer, is the forward thinker. I am horribly guilty this year of constantly being nostalgic about my own past abilities. When I start writing an outline or a draft, I find myself thinking, what's wrong with me, why can't I do this? I used to be great at doing this. The forward writer is a brilliant way to logically organize the content. I need a way to combat the "backward thinker". Any suggestions?

In response to Vanessa's comment, I suggest Vipassana meditation. It's a practice of training oneself to observe all of one's thinking (but particularly, in Vanessa's case, it would be ruminative, self-defeating thinking) come and go, without judging it. Over time, this conditioning makes it easier to let go of thoughts that get in the way of whatever one is intending to do. More here: http://www.dharma.org/ (included as a resource; I am not affiliated).

Post a Comment